How long ago was 1997 in the baseball card world? To start, there were six manufacturers producing MLB-licensed baseball cards, the most ever in the history of the hobby. There were only 28 Major League Baseball teams. The Red Sox hadn’t won a World Series in forever. The Brewers were in the American League. Baseball was still recovering from the strike that cut the 1994 season short. And nobody had ever crammed a piece of a baseball uniform into a piece of cardboard.

The story really begins all the way back in 1990. Upper Deck, in its second year of production after shaking up the industry with its debut set, was in need of a draw for its high number packs, which had the same mix of cards as the regular packs plus some from 100 more cards of nobodies and has-beens. Their solution was a ten-card insert set honoring all-time great Reggie Jackson plus an additional variant card personally autographed by Mr. October – the first-ever certified autograph insert. Now, insert cards were nothing new; various insert sets appeared in sets during the ’80s with little or no fanfare, often confusing kids who pulled a card that didn’t look anything like the others. Something amazing happened to the Reggie Jackson Baseball Heroes set though – it became a hit. The world’s first commercially successful insert set was born and the hobby would never be the same.

Certified autograph cards would remain fairly rare for the rest of the decade, but inserts quickly became a set’s main draw, overshadowing even rookie cards (particularly when the inserts featured rookies, as in Fleer’s once-hot but now-forgotten Rookie Sensations insert set). As manufacturers churned out more and more sets (with smaller and smaller production runs), inserts flooded the market, making collecting cards of even a single player an impossible task. The insert arms race was well underway.

By the middle of the decade, ordinary inserts and foil-stamped parallel sets were commonplace. There were hobby-exclusive inserts, retail-exclusive inserts, jumbo pack exclusives, rack pack exclusives, and all sorts of other meaningless distinctions. Upper Deck tried to capitalize on its hologram fetish with limited success. Topps had better luck with its Refractor parallel cards (which only came in one variety of rainbow-reflective chrome, unlike the countless variants in today’s sets). Upper Deck tried to tie player performance to mail-in bonus offers with its Predictor cards, but those didn’t last too long. Many other gimmicks made their way into cards in these years, including various materials (real and simulated), foil, embossing, die-cut cards, and more, but none were game-changers. Until 1997 (well, technicaly late 1996, but close enough).

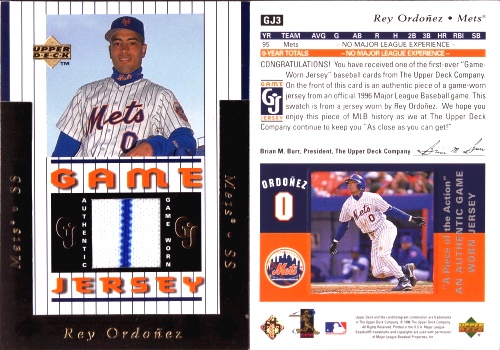

In retrospect, the concept seems obvious. Take a piece of cardboard with a player’s name and picture on it, add a tiny piece of game-used equipment, profit! Following their experiment in the 1996-1997 Football set, Upper Deck tested the baseball waters in 1997 with a three-card UD Game Jersey set featuring some can’t-miss stars. The plan seemed to be to feature one veteran star, one young star, and one star prospect. For the veteran star, they chose Tony Gwynn. Gwynn isn’t a bad choice, but his Hall of Fame classmate Cal Ripken Jr. was probably more relevant at the time, having recently broken Gehrig’s consecutive game streak and all. For the young star, they went with face-of-the-brand Ken Griffey Jr., of course. And for the prospect, they picked a New York shortstop in pinstripes who was coming off an impressive rookie season in 1996. No, not the one who was named Rookie of the Year and would go on to rack up 3000 hits and almost as many World Series rings as he had fingers in the course of a Hall of Fame career. No, they rounded out this historic set with Rey Ordoñez.

The first Mets jersey available in bite-size pieces

And so the first-ever Mets pinstripe jersey card came into being. Gwynn cruised into the Hall of Fame alongside Ripken. Griffey had a few more seasons as the best player in baseball before his non-steroid-enhanced body succumbed to age and injury on his way to the Hall. And Rey Ordoñez missed most of the one season his team made it to the World Series due to injury, only to return to have broadcasters make “and this is the kind of play that Ordoñez makes look easy” or “and this is why the Mets can afford to let him swing a limp noodle of a bat” comments right before misplaying a ball that the pre-injury Ordoñez would have gotten to easily. Sometimes the cards end up being more notable than the players.

Recent Comments